Particularly if you live in the Northeast, you might notice that it is really hot out. And buggy.

Much of the United States has gotten a lot of rain this summer, too, providing breeding ground for mosquitoes. At some point, it’s expected that some of these mosquitoes could start carrying the Zika virus. Zika’s outbreak, which started last fall in Brazil, has caused at least three infants in the United States — and thousands across South and Central America — to be born with microencephaly, a defect characterized by incomplete growth of the head and brain, and which is linked to many health complications.

Understandably, people are worried.

The House of Representatives recently passed a piece of legislation that would allow people to more freely use pesticides — without clearing the use with the EPA. But similar legislation has been introduced in the House five times over the past several years, and opponents say it is less a measure to protect Americans against Zika than a free pass to pollute the country’s water. There are already more than a thousand waterways in the United States that are impaired because of pesticide use. Additional use would likely impact fishing, recreation, and human health.

It’s also hard to believe this bill signifies Congress’ commitment to fighting Zika, since the body hasn’t yet agreed to fund an emergency package.

But it turns out that there is a hero people can turn to: a flying, furry mammal.

Bats get a bad rap. They have been linked to vampires. They are associated with a vengeful superhero. They appear at night, tapping into our deepest fears. They very occasionally carry rabies.

But they are also awesome. A single bat can eat up to 1,000 mosquitoes an hour. That’s a mosquito every 3.6 seconds. In the time it has taken to read this far, a bat has eaten 10 mosquitoes — more than enough to ruin a picnic.

While no one is sure what caused the Zika outbreak, the spread of the disease can be tied to climate change. In fact, a recent study from across several scientific and health agencies indicated that climate change is going to significantly increase the risk of vector-borne diseases, which are carried by mosquitoes and ticks, in the coming years.

“We are going to see diseases in areas we haven’t seen them before,” said Juli Trtranj, a NOAA scientist who worked on the report. As the climate changes, more areas of the United States will be hospitable to the mosquitoes and ticks, and the season of risk will be longer.

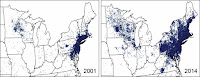

Maps show the reported cases of Lyme disease in 2001 and 2014 for the areas of the country where Lyme disease is most common (the Northeast and Upper Midwest). Both the distribution and the numbers of cases have increased. (Figure source: adapted from CDC 2015) Maps show the reported cases of Lyme disease in 2001 and 2014 for the areas of the country where Lyme disease is most common (the Northeast and Upper Midwest). Both the distribution and the numbers of cases have increased. (Figure source: adapted from CDC 2015) (Credit: The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in The United States: a Scientific Assessment)

Bats are a great, natural, pesticide-free defense against mosquitoes, but they are also in danger. In less than a decade, millions of bats across 25 states and five Canadian provinces have died from white nose syndrome. Bats are being infected by white fungus on the skin of their noses, ears, and wings. Authorities have no idea why white nose syndrome has emerged in recent years. According to the National Wildlife Federation, at least nine species of bats in the United States are endangered. Largely, as usual, because of human disruption to habitat.

And, as with so many other animals (including humans), climate change is making life more difficult for the bats that are left. Not only are their hibernation cycles and geographic ranges being disrupted, one recent study found that warming habitats can interfere with bats' echolocation system — the thing that allows them to fly around at night.

Which is why it's even more important that people embrace these furry, often blind, amazing little creatures. Not only are they potentially saving us, we can help save them.

Read more at Climate Change, Bats, and Zika: 2016’s Weirdest Relationship

No comments:

Post a Comment