A geologist explains that climate change is not just about a global average sea rise.

Jerry Mitrovica has been overturning accepted wisdom for decades. A solid Earth geophysicist at Harvard, he studies the internal structure and processes of the Earth, which has implications for fields from climatology to the timing of human migration and even to the search for life on other planets. Early in his career he and colleagues showed that Earth’s tectonic plates not only move from side to side, creating continental drift, but also up and down. By refocusing attention from the horizontal of modern Earth science to the vertical, he helped to found what he has nicknamed postmodern geophysics. Recently Mitrovica has revived and reinvigorated longstanding insights into factors that cause huge geographic variation in sea level, with important implications for the study of climate change today on glaciers and ice sheets.

...

Some of your recent research follows from the attraction of ocean water to ice sheets. That seems surprising.

This is just Newton’s law of gravitation applied to the Earth. An ice sheet, like the sun and the moon, produces a gravitational attraction on the surrounding water. There’s no doubt about that.

What happens when a big glacier like the Greenland Ice Sheet melts?

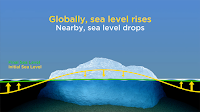

Three things happen. One is that you’re dumping all of this melt water into the ocean. So the mass of the entire ocean would definitely be going up if ice sheets were melting—as they are today. The second thing that happens is that this gravitational attraction that the ice sheet exerts on the surrounding water diminishes. As a consequence, water migrates away from the ice sheet. The third thing is, as the ice sheet melts, the land underneath the ice sheet pops up; it rebounds.

So what is the combined impact of the ice-sheet melt, water flow, and diminished gravity?

Gravity has a very strong effect. So what happens when an ice sheet melts is sea level falls in the vicinity of the melting ice sheet. That is counterintuitive. The question is, how far from the ice sheet do you have to go before the effects of diminished gravity and uplifting crust are small enough that you start to raise sea level? That’s also counterintuitive. It’s 2,000 kilometers away from the ice sheet. So if the Greenland ice sheet were to catastrophically collapse tomorrow, the sea level in Iceland, Newfoundland, Sweden, Norway—all within this 2,000 kilometer radius of the Greenland ice sheet—would fall. It might have a 30 to 50 meter drop at the shore of Greenland. But the farther you get away from Greenland, the greater the price you pay. If the Greenland ice sheet melts, sea level in most of the Southern Hemisphere will increase about 30 percent more than the global average. So this is no small effect.

What happens with melting in Antarctica?

If the Antarctic ice sheets melt, sea level falls close to Antarctic. But it would rise more than you’d otherwise expect in the Northern Hemisphere. These are known as sea-level fingerprints, because each ice sheet has its own geometry. Greenland produces one geometry of sea level change and the Antarctic has its own. Mountain glaciers have their own fingerprint. This explains a lot of variability in sea level. It’s also a really important opportunity. If you have people denying climate change because they say there’s geographic variation in sea level changes—it doesn’t go up uniformly—you can say, “Well, that is incorrect because ice sheets produce a geographically variable change in sea level when they melt.” You can also use that variability to say this percentage is coming from Greenland, this percentage is coming from the Antarctic, and this percentage is coming from mountain glaciers. You can source the melt. And that’s an important argument from a public-hazard viewpoint.

Read more at Why Our Intuition About Sea-Level Rise Is Wrong

No comments:

Post a Comment