Perhaps the first clear sign that the United States is considering serious changes in the way it forecasts extreme weather events came in a meeting here in June 2015. It featured a blunt-spoken Australian meteorologist, Greg Holland, who ticked off the flaws in the current U.S. system.

There are serious problems with the nation's climate models, he noted. While they're pretty good on forecasting some things, such as rising temperatures, "they're actually crap on rainfall," he said, noting that models have failed to predict major droughts. One was the worst in U.S. history, the Great Plains Drought of 2012.

Predictions of hurricanes dwell on wind speed but tend to ignore aspects such as the slow movement and size of a storm, aspects that can create storm surges that lead to more severe damage and loss of life, he asserted. Moreover, the models have grown too big, nonspecific and complex to give much warning or help to community leaders struggling to protect their cities or towns against a major storm.

Then there are the communities themselves. As Holland put it: "We have had a massive loss in society resiliency. The U.S. a hundred years ago could recover from [weather] systems far better than any society that we've got in any major city can now. It's partly because we've forgotten how to recover. It's also partly because we're so bloody complicated now that it's really harder to recover."

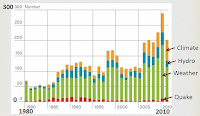

The problem cuts across business, agriculture, transportation and other sectors, as well, Holland said. While plans for forecasting and dealing with extreme weather haven't changed much in the last 50 years, the damage from storms has almost quadrupled globally. As things stand, Holland predicted, the United States is heading for more change and uncertainty in the form of extreme weather events.

"Across all of this," Holland noted, "is the lack of communication."

A few months later, the National Academy of Sciences underscored Holland's concerns by publishing a plan to engage users of weather forecasts in helping to develop more accurate, long-term forecasts and to increase their predictive skills for extreme weather. One of the sponsors of the academy's plan was the Pentagon, in the form of the Office of Naval Research.

Coupling computer models with a broader array of data from the Earth's surface and atmosphere, the academy noted, is a technique "still in its infancy, but has the potential to spur a more dramatic leap forward."

There's an app for that

That is a complex area, but one of the leaders in it is Holland. Meteorologists, businessmen and planners listen to Holland, a scientist whose career has been an Australian-American amalgam of innovation and work with both Australia's Bureau of Meteorology Research Centre and the Boulder-based National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), where he is leading the formation of a new government/business partnership.

The goal: to bring in the more serious users of weather forecasts. It is called Engineering for Climate Extremes Partnership (ECEP).

...

Climate scientists are also attracted to Holland's new partnership approach because it helps get their discoveries out more quickly and into the hands of people who can use them. "Usually when I finish my work I write a paper and nobody beyond scientific colleagues reads it," explained Debasish PaiMazumder, a drought expert and one of a number of scientists working at ECEP on specific problems.

Instead, PaiMazumder finished one recent study by designing a specific tool: It is an application called "Climate Eye" that is slated for a website ECEP is building. PaiMazumder hopes his app will help construction companies such as Accame's prepare for and thus reduce their losses from extreme weather events.

A second Climate Eye is being designed for farmers and agricultural companies to get better seasonal predictions that will help them prepare for and thus mitigate extreme weather threats, such as droughts and heat waves that are likely to reduce production in specific regions, or to threaten specific crops.

Other apps in the works at ECEP will help specific cities to more effectively plan for damage from hurricanes where storm-driven surges and flooding and the peculiarities of local topography are factors that cause the most damage. One will allow the city of Brisbane, Australia, to run computer models of specific storms against the city's defenses to better appreciate the quirks and power of future storms.

...

In 2005 Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans and killed more than 1,800 people in six Gulf Coast states. The storm cost the federal government over $105 billion and private insurers $41 billion. Katrina caused the largest aggregate loss in the history of insurance.

While Katrina was better predicted than previous storms, it arrived earlier than forecast, giving planners only 2.5 days of warning, and created a storm surge that collapsed the city's levees. "This was a real world scenario that the models hadn't taken into account," explained a later study done by ECEP.

The upshot of these two experiences, according to Holland, is that ECEP's partnership is aimed at seeking an enlarged dialogue among businesses, insurers, scientists, universities, and governments. He wants to develop better cat models, some of which ECEP will put in the public domain. The combined effort will be guided by a philosophy that he calls "graceful failure," an approach that gives communities a plan B to help save lives and restrict damage, rather than relying on one defense alone, as New Orleans did with its levees.

Read more at Who Cares If It's Climate Change? This Guy Wants Action

No comments:

Post a Comment